An Old Educator's Thoughts on Reading Instruction

After teaching nearly 30 years, I must admit I am totally confused by the debate over reading instruction. Maybe I am missing something? Balanced Literacy vs. Scientific Methods?

Over the last 10 years of my long career, I observed that whenever the a specific reading program was dictated, success, often defined by scores on standardized tests, was fleeting. When I worked in a school where the school leaders had worked in classrooms, and as admins continued to spend extended times actually doing the work of teaching, I thought I had achieved nirvana. The training and discussions were rich and deep. I felt supported to try new approaches when they made sense for my students.

We taught reading under the umbrella of using a balanced literacy approach.

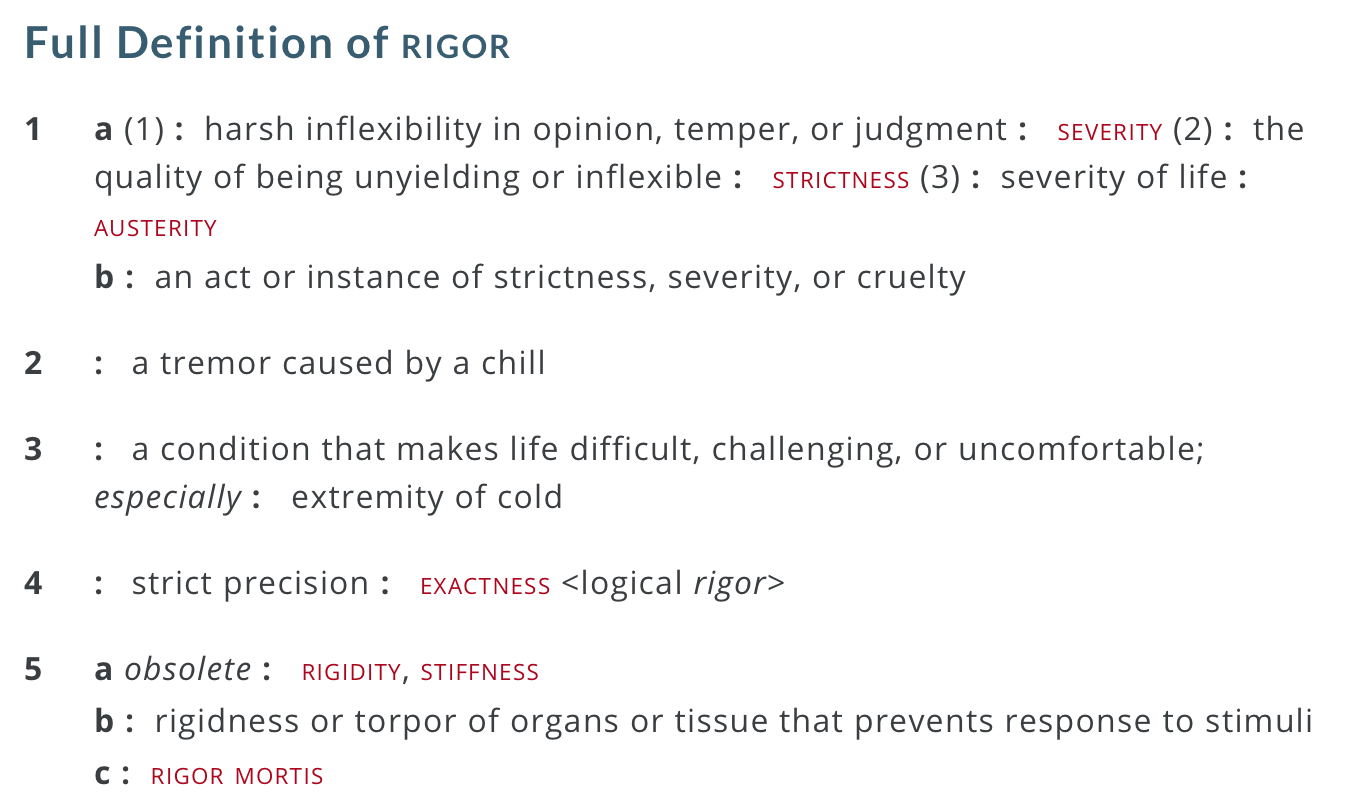

BALANCED literacy includes effective instruction in five essential components: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. If reading instruction is effective, an essential descriptor for successful reading instruction, all of these five elements must be included in instruction. Those same elements are part of a scientifically based reading program, but the difference, I believe is that the scientifically based programs include ongoing research and are spelled out more sequentially. An example would be Orton Gillingham.

For those outside of education, to insinuate that phonics is not a part of a balanced reading program is a misconception. And the implication that schools should offer explicit phonics instruction as the only decoding strategy is likewise unrealistically narrow.

I’ve recently read disparaging comments that students are taught “decoding strategies” in place of phonics - which is in my experience, untrue - and uninformed. As an elementary teacher I found explicitly teaching students to use decoding strategies, including, but not limited to phonics, was a pedagogical decision that I continue to feel made sense. Teaching a variety of strategies to decode texts is essential to becoming a fluent reader with good comprehension skills. When I reflect on my own practice as an adult reader, considering what my brain does when I encounter an “unknown”, I use one or more of these skills regularly. For example, when reading a text and encountering a word or term from another language, I often skip and return or use context clues.

Why wouldn’t I teach students that these strategies are what accomplished readers use, too?

When a program is determined to be Scientifically based, there is on-going research that provides an analysis of effective pedagogy. The same five components of reading are included with the emphasis on continued research and evaluation how effective these strategies are. Scientifically based reading is NOT a specific program, although I’m sure there are textbook publishers that would like one to believe otherwise. As educators and educational researchers learn more about how to effectively teach reading, it will continue to change. Educators adapt reading instruction to reflect new understandings, and most importantly to address the needs of the students they work with.

And this is why, for me, teaching reading has always been somewhat of an art as well as a science. No matter what it is called, reading instruction needs to be effective and to include the essential aspects of learning to be literate

Senator Charles Shumer and Representative Nancy Pelosi have published their collective ideas supporting public education. Their 5-point proposal can be found in

Senator Charles Shumer and Representative Nancy Pelosi have published their collective ideas supporting public education. Their 5-point proposal can be found in  Some years ago, I enrolled in an Italian language class at Boston Language Institute. The class met for 3 hours - no break - several times each week. The instructor only spoke my "new" language, Italian, for the entirety of the three hours. We had some written materials, some listening resources, but mainly we were expected to immerse ourselves in Italian. If this sounds like what happens in a classroom, I would agree.The first thing I learned from this experience was how utterly frustrating it is for a learner to function outside of his or her native language. But one of the larger experiences for me was the chance to experience what it must feel like for a student to attempt to sustain concentration and focus for extended stretches of time without a break.By Hour 2 of my 3-hour class, I felt hopeless and defeated. I could no longer take another idea into my brain. I left the class with a dull and aching head and lots of questions as to what the goal of that instruction was. If this was my experience with sustained time-on-task learning as an adult, it wasn't hard to imagine the same sense of frustration and defeat applying to the young learners in my classroom.Regardless of whether or not the student is learning in a non-native language, as many of my former students were, extended periods of concentration does not necessarily yield higher academic achievement. Whether adult or child, the brain needs what the brain needs. And in learning new things, the brain needs some time off to make connections and absorb learning.Since the inception of education reform, standardized curriculum, and high-stakes testing, educators have been pressured to prove that students are learning. The proof has, to date, been in the form of high stakes testing. Students, teachers, and schools who do not achieve arbitrary scores indicating that the prescribed curriculum has been mastered are called out. The trickle down response to test scores that are less than stellar has been toward reducing or eliminating children's recess time.Why? Because when test scores look bad, the first response is that the students need "more time" to learn the material. That time has to come from somewhere, so shaving minutes away from recess is the first response. To me, this sounds a lot like what I did as an unprepared college student studying for a final in Western Civilization: cramming.Reducing or eliminating students' active time does not mean better test results. The brain needs some time to process and absorb new learning. Kids who fidget less, focus more.So what our kids need is similar to what my experience as a student proved for me: more recess. Don't take my word for it. Here's a statement from a recent

Some years ago, I enrolled in an Italian language class at Boston Language Institute. The class met for 3 hours - no break - several times each week. The instructor only spoke my "new" language, Italian, for the entirety of the three hours. We had some written materials, some listening resources, but mainly we were expected to immerse ourselves in Italian. If this sounds like what happens in a classroom, I would agree.The first thing I learned from this experience was how utterly frustrating it is for a learner to function outside of his or her native language. But one of the larger experiences for me was the chance to experience what it must feel like for a student to attempt to sustain concentration and focus for extended stretches of time without a break.By Hour 2 of my 3-hour class, I felt hopeless and defeated. I could no longer take another idea into my brain. I left the class with a dull and aching head and lots of questions as to what the goal of that instruction was. If this was my experience with sustained time-on-task learning as an adult, it wasn't hard to imagine the same sense of frustration and defeat applying to the young learners in my classroom.Regardless of whether or not the student is learning in a non-native language, as many of my former students were, extended periods of concentration does not necessarily yield higher academic achievement. Whether adult or child, the brain needs what the brain needs. And in learning new things, the brain needs some time off to make connections and absorb learning.Since the inception of education reform, standardized curriculum, and high-stakes testing, educators have been pressured to prove that students are learning. The proof has, to date, been in the form of high stakes testing. Students, teachers, and schools who do not achieve arbitrary scores indicating that the prescribed curriculum has been mastered are called out. The trickle down response to test scores that are less than stellar has been toward reducing or eliminating children's recess time.Why? Because when test scores look bad, the first response is that the students need "more time" to learn the material. That time has to come from somewhere, so shaving minutes away from recess is the first response. To me, this sounds a lot like what I did as an unprepared college student studying for a final in Western Civilization: cramming.Reducing or eliminating students' active time does not mean better test results. The brain needs some time to process and absorb new learning. Kids who fidget less, focus more.So what our kids need is similar to what my experience as a student proved for me: more recess. Don't take my word for it. Here's a statement from a recent  I started reading

I started reading  Is STEM the only thing? I'm asking for a friend.It occurs to me that in the rush to turn out worker bees for business sectors, the focus in education is more than a little skewed in favor of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Yes, these are all important studies and part of a well-rounded balanced education. However, I am questioning that the focus on STEM has over-shadowed other content and curricula that, in my biased opinion, should be equally important.Because I see education in terms of an avenue toward a pursuit, observing the march of the bureaucrats toward the next great crisis in education is equally frustrating and alarming. Our educational goal should be to "hook" students into becoming life-long students, to foster curiosity and questioning and the drive to know more.And maybe that pathway toward becoming lifetime learners is through a STEM discipline, and perhaps it is not.As a student, my personal pathway into learning was through something quite different. I was a more-than-adequate reader, not a particularly skilled writer, and a horribly incompetent math student. What fired me up to become more disciplined about learning and more successful as a student, was a love and pursuit of music. The irony of this statement is that, as an adult, music has taken a backseat to the very disciplines that catch all the attention today - technology and mathematics.To me, it is more important to teach students to think critically, to process logically and, yes, even scientifically. Science, math, and technology are important and great ways to get to those problem-solving and thinking skills. But other disciplines can be a means to this end - and toward the goal of fostering and enduring desire to learn - too. And for the student whose interest in learning lies in arts and humanities, exclusion of such pursuits leave them flat.So while our education policy makers direct a refocus on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, I hope there might also be a similar pursuit of arts and humanities. Because, in my opinion, there is a need to balance educational pursuits across all disciplines.

Is STEM the only thing? I'm asking for a friend.It occurs to me that in the rush to turn out worker bees for business sectors, the focus in education is more than a little skewed in favor of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Yes, these are all important studies and part of a well-rounded balanced education. However, I am questioning that the focus on STEM has over-shadowed other content and curricula that, in my biased opinion, should be equally important.Because I see education in terms of an avenue toward a pursuit, observing the march of the bureaucrats toward the next great crisis in education is equally frustrating and alarming. Our educational goal should be to "hook" students into becoming life-long students, to foster curiosity and questioning and the drive to know more.And maybe that pathway toward becoming lifetime learners is through a STEM discipline, and perhaps it is not.As a student, my personal pathway into learning was through something quite different. I was a more-than-adequate reader, not a particularly skilled writer, and a horribly incompetent math student. What fired me up to become more disciplined about learning and more successful as a student, was a love and pursuit of music. The irony of this statement is that, as an adult, music has taken a backseat to the very disciplines that catch all the attention today - technology and mathematics.To me, it is more important to teach students to think critically, to process logically and, yes, even scientifically. Science, math, and technology are important and great ways to get to those problem-solving and thinking skills. But other disciplines can be a means to this end - and toward the goal of fostering and enduring desire to learn - too. And for the student whose interest in learning lies in arts and humanities, exclusion of such pursuits leave them flat.So while our education policy makers direct a refocus on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, I hope there might also be a similar pursuit of arts and humanities. Because, in my opinion, there is a need to balance educational pursuits across all disciplines. Educators, if you received a free and unsolicited book in the mail, would you read it? That's what a conservative "climate realist" group by the name of Heartland Institute wants you to do. In fact, it would be really swell if teachers would do a little more than just read their free book(s). If you would also start teaching some of their conceptions and beliefs, that would be great.Here's an introduction to this Heartland Institute courtesy of

Educators, if you received a free and unsolicited book in the mail, would you read it? That's what a conservative "climate realist" group by the name of Heartland Institute wants you to do. In fact, it would be really swell if teachers would do a little more than just read their free book(s). If you would also start teaching some of their conceptions and beliefs, that would be great.Here's an introduction to this Heartland Institute courtesy of  I was thinking about

I was thinking about

Play - real, unstructured brain break time - is as important to a child's learning as academic time.So why are school leaders and decision-makers so reluctant to let go and allow more recess? I cringe whenever I hear a school leader lecture that there isn't enough time in a school day to increase play or unstructured time. Two reasons come to mind:

Play - real, unstructured brain break time - is as important to a child's learning as academic time.So why are school leaders and decision-makers so reluctant to let go and allow more recess? I cringe whenever I hear a school leader lecture that there isn't enough time in a school day to increase play or unstructured time. Two reasons come to mind:

So, what would you say an unexpected by-product of ed reform might be? With loss of autonomy in what to teach when, emphasis on high-stakes standardized testing and little control over just about anything else in the educational day, teachers are leaving some districts for transfers to more affluent schools and for other careers.I mention this because it is challenging to teach in a gateway - or as the Pioneer Institute referred to it last week "middle" - city. And because the Lowell Schools are making an effort to diversify faculty and staff.

So, what would you say an unexpected by-product of ed reform might be? With loss of autonomy in what to teach when, emphasis on high-stakes standardized testing and little control over just about anything else in the educational day, teachers are leaving some districts for transfers to more affluent schools and for other careers.I mention this because it is challenging to teach in a gateway - or as the Pioneer Institute referred to it last week "middle" - city. And because the Lowell Schools are making an effort to diversify faculty and staff. Ludlow Superintendent Todd Gazda posed this question in a recent Commonwealth Magazine article: What is equity? Because, as Dr. Gazda points out, current education policy tends toward equalizing education for all students with standardized curriculums proven by standardized assessment and incentivized "business systems" for implementation.

Ludlow Superintendent Todd Gazda posed this question in a recent Commonwealth Magazine article: What is equity? Because, as Dr. Gazda points out, current education policy tends toward equalizing education for all students with standardized curriculums proven by standardized assessment and incentivized "business systems" for implementation.

As a writer and, as a teacher, I value collaboration with peers. I know that my writing is made more clear, more interesting, and more precise when I rely on a trusted "critical friend" to offer constructive feedback. And so, when the Commonwealth's writing standards included peer revising as well as adult conferring, the inclusion of critical friends in the Writing Process made sense. Beginning in Grade 2, Writing Standard 5 includes this important progression of peer revision and peer editing. [Refer to the Writing Standards ("Code W") by grade level beginning on page 26 of the

As a writer and, as a teacher, I value collaboration with peers. I know that my writing is made more clear, more interesting, and more precise when I rely on a trusted "critical friend" to offer constructive feedback. And so, when the Commonwealth's writing standards included peer revising as well as adult conferring, the inclusion of critical friends in the Writing Process made sense. Beginning in Grade 2, Writing Standard 5 includes this important progression of peer revision and peer editing. [Refer to the Writing Standards ("Code W") by grade level beginning on page 26 of the